Leaving Trouble for Tomorrow

The girls and I arrived in Alaska two weeks ago. Along with a stroller, four carry-ons, a duffel-sized bag of snacks, a card that explains why Anna sets off metal detectors, and four suitcases, I also nestled--between sweatshirts and a wetsuit--an expensive, lent-out tablet that I'll be using to program Anna's cochlear implants remotely. Using Wifi, we'll video chat with her audiologist, plug the implants into a special chord on one end and her head on the other, and we'll be able to see how close her MAP is to what her brain needs to receive sound. Allison, our audiologist, can change the levels of the cochlear implants from Colorado; each of the 44 electrodes in Anna's head indicate, onscreen, the optimum settings for her to hear normally by August.

When we left Colorado, I asked Allison if we should continue coming up here to Alaska when it might best serve Anna to be home where all our specialists are. But it turns out, remote MAPing is something audiologists are quite used to, as they have to do appointments at a distance for every rural deaf child in Colorado. Allison is Canadian and grew up at the same latitude as where we live in Sitka. She wants me to hold up the tablet while we're talking next week and show her what it looks like. If it's a day like today, the sky is like a dimensionless rectangle, a thick white poster board onto which have been etched dark blue mountains with slopes of an Irish green. Luke has the day off and he took Zaley down to the boat with his brother Max, who is here for a month fishing.

The girls and I arrived in Alaska two weeks ago. Along with a stroller, four carry-ons, a duffel-sized bag of snacks, a card that explains why Anna sets off metal detectors, and four suitcases, I also nestled--between sweatshirts and a wetsuit--an expensive, lent-out tablet that I'll be using to program Anna's cochlear implants remotely. Using Wifi, we'll video chat with her audiologist, plug the implants into a special chord on one end and her head on the other, and we'll be able to see how close her MAP is to what her brain needs to receive sound. Allison, our audiologist, can change the levels of the cochlear implants from Colorado; each of the 44 electrodes in Anna's head indicate, onscreen, the optimum settings for her to hear normally by August.

When we left Colorado, I asked Allison if we should continue coming up here to Alaska when it might best serve Anna to be home where all our specialists are. But it turns out, remote MAPing is something audiologists are quite used to, as they have to do appointments at a distance for every rural deaf child in Colorado. Allison is Canadian and grew up at the same latitude as where we live in Sitka. She wants me to hold up the tablet while we're talking next week and show her what it looks like. If it's a day like today, the sky is like a dimensionless rectangle, a thick white poster board onto which have been etched dark blue mountains with slopes of an Irish green. Luke has the day off and he took Zaley down to the boat with his brother Max, who is here for a month fishing.

Today is what my friend Sara (who lives on a remote Alaskan island with her three children where her husband setnet fishes) calls a "grace day." Today, Luke let me sleep in till 7:30. Today, I have the relief that ceases the hour-counting I often can't help with young children in a rainy town: half-an-hour till the library opens. 2 more hours till lunch time. 3 more hours till nap time. Today, I have time to have a cup of coffee while the baby is sleeping instead of gulping it between "mmm's" and "eee-eee-eee-ooh-ooh-ooh's" and "buh-buh-buh's"--all the sounds I ascribe to animals and vehicles I pull from a box to "check in" with Anna's hearing every morning. Today, Anna is asleep without the threat of Zaley's footsteps waking her. Today is a grace day, when lots of others days, I am asking for grace because I'm finding little.

Today is what my friend Sara (who lives on a remote Alaskan island with her three children where her husband setnet fishes) calls a "grace day." Today, Luke let me sleep in till 7:30. Today, I have the relief that ceases the hour-counting I often can't help with young children in a rainy town: half-an-hour till the library opens. 2 more hours till lunch time. 3 more hours till nap time. Today, I have time to have a cup of coffee while the baby is sleeping instead of gulping it between "mmm's" and "eee-eee-eee-ooh-ooh-ooh's" and "buh-buh-buh's"--all the sounds I ascribe to animals and vehicles I pull from a box to "check in" with Anna's hearing every morning. Today, Anna is asleep without the threat of Zaley's footsteps waking her. Today is a grace day, when lots of others days, I am asking for grace because I'm finding little.

When we flew into Sitka last week, I was filled with the familiar cocktail of dread and love for this place. It was partly cloudy and I could see the sharp tip of Mount Verstovia, still covered in shoots of snow since it's earlier this year than I've come up in a while. We could see a silver boat cutting towards the airport and Zaley pointed and yelled, "That's my Daddy!" Around us on the plane, we could feel the excited buzz of people coming to Alaska for the first time, the epic-ness of their adventure just beginning. I remember my first time coming here and how my love for Luke and the beauty of the place were a physical sensation pounding out in my chest as the plane began to descend.

These sensations are both still present every time I arrive. But every year, there is another layer of memories and complications through which I feel the thrill. Here is the yellowed roof of the hospital where we discovered Anna's differences last year, where I sat through an ultrasound that would tell us if she would have cognitive delays for the rest of her life. Here is the bridge rising over the channel where I rode with her crying in the back of the car, for the first time understanding that it was a soundless action to her, a release of silence accompanied by an open mouth and once the car stopped,

These sensations are both still present every time I arrive. But every year, there is another layer of memories and complications through which I feel the thrill. Here is the yellowed roof of the hospital where we discovered Anna's differences last year, where I sat through an ultrasound that would tell us if she would have cognitive delays for the rest of her life. Here is the bridge rising over the channel where I rode with her crying in the back of the car, for the first time understanding that it was a soundless action to her, a release of silence accompanied by an open mouth and once the car stopped,  the magical appearance of a mom. Here is the house that I love, with the same baked-bread smell as last summer, a humid warmth, the same seaside view, the tall windows that I wake to each morning, the indigo ridges of the mountains so defined and so close they are usually visible even through a heavy settle of fog. Here is the lighthouse, steady as ever, red-trimmed, where Zaley wants to pull up a boat and live. Here is the beauty that can be both saving and shaming. How can I struggle so much to love a place so authentic, so exquisite?

the magical appearance of a mom. Here is the house that I love, with the same baked-bread smell as last summer, a humid warmth, the same seaside view, the tall windows that I wake to each morning, the indigo ridges of the mountains so defined and so close they are usually visible even through a heavy settle of fog. Here is the lighthouse, steady as ever, red-trimmed, where Zaley wants to pull up a boat and live. Here is the beauty that can be both saving and shaming. How can I struggle so much to love a place so authentic, so exquisite?

Last week, we met my good friend Lisa down on Magic Island--one of many rocky beaches here that, at low tide, connects by a sandy spit to a smaller, explorable island. Zaley is easier this year, less afraid of crabs, more imaginative, loves to perform "releve's" with her hands above her head and her feet lifted at the heels. Last week was the last time Zaley would play with Lisa's kids because their dad, a pilot for the Coast Guard, accepted a job on the East Coast.  Lisa and I talk about the struggles of motherhood, the way our children's stories are not our own (much as we try to make them), the way we have both struggled to find God in a place so beautiful and yet so difficult. She told me something her husband said to her as they get ready to transition their family to a completely new place, somewhere that will be nothing like Alaska. Lisa worries about her oldest kids in high school. I worry about the pink that has showed up in Anna's eye, how maybe it will become one more, unexpected cmv-thing: like the sneaking up of her total loss of hearing, what if this symptom (very likely just conjunctivitis from a recent cold) is going to become a permanent loss of vision? What if this is the first sign of her blindness? I don't want to lose anything else of Anna's in Alaska. Lisa's husband had said to her, as she worried about every ensuing year: "Don't borrow tomorrow's troubles."

Lisa and I talk about the struggles of motherhood, the way our children's stories are not our own (much as we try to make them), the way we have both struggled to find God in a place so beautiful and yet so difficult. She told me something her husband said to her as they get ready to transition their family to a completely new place, somewhere that will be nothing like Alaska. Lisa worries about her oldest kids in high school. I worry about the pink that has showed up in Anna's eye, how maybe it will become one more, unexpected cmv-thing: like the sneaking up of her total loss of hearing, what if this symptom (very likely just conjunctivitis from a recent cold) is going to become a permanent loss of vision? What if this is the first sign of her blindness? I don't want to lose anything else of Anna's in Alaska. Lisa's husband had said to her, as she worried about every ensuing year: "Don't borrow tomorrow's troubles."

This, I believe, is easier for men and children than it is for women. In a mother's world, today's troubles--a short nap, an eye that goes unchecked--become tomorrow's. He's right, of course, that today is more important than fear, but this is a hard hard lesson for me. I have already plotted out my happiness according to Luke's days off. The following two weeks (no days off) will be difficult.

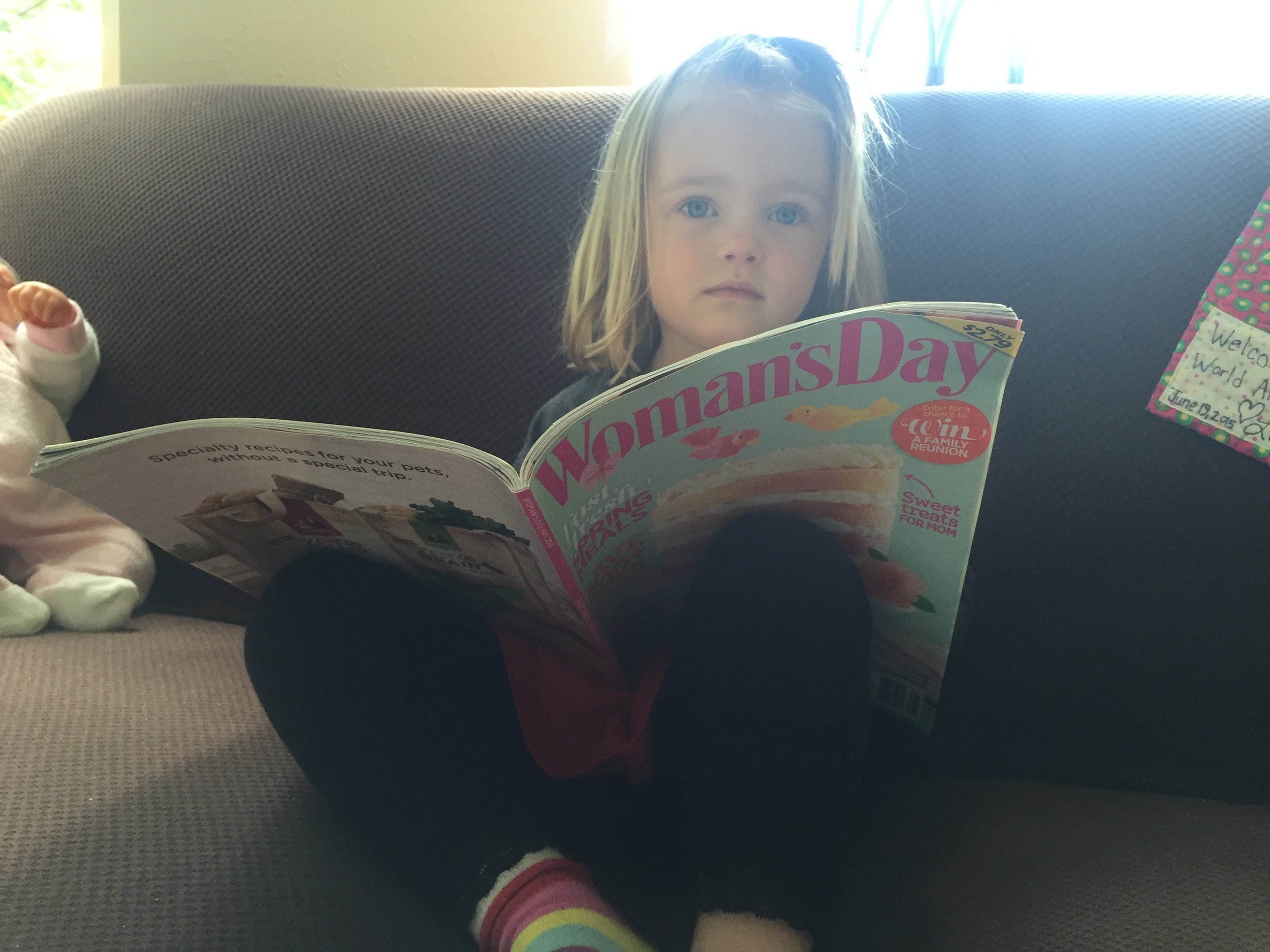

This, I believe, is easier for men and children than it is for women. In a mother's world, today's troubles--a short nap, an eye that goes unchecked--become tomorrow's. He's right, of course, that today is more important than fear, but this is a hard hard lesson for me. I have already plotted out my happiness according to Luke's days off. The following two weeks (no days off) will be difficult.  Early July is glorious, with five days in a row, even if he'll be commercial fishing for some of them. In front of me, Zaley wants to know what's for lunch, if I'll play librarian with her. Anna chuckles--an excited, panting-type laugh, with tongue out--when we are eating and she hears us saying "mm, mmm, mmmmmm." She is lifting her arms, face beaming, when I say, "up!" Children don't know what's next, ever. I envy them their unawareness of the future, the way a simple action, a gentle lifting up from a chair, is all that's needed for them to feel joy. At the same time, I don't envy them because receiving their joy also brings it to me in a way I never experienced--especially here in Sitka--before I had kids.

Early July is glorious, with five days in a row, even if he'll be commercial fishing for some of them. In front of me, Zaley wants to know what's for lunch, if I'll play librarian with her. Anna chuckles--an excited, panting-type laugh, with tongue out--when we are eating and she hears us saying "mm, mmm, mmmmmm." She is lifting her arms, face beaming, when I say, "up!" Children don't know what's next, ever. I envy them their unawareness of the future, the way a simple action, a gentle lifting up from a chair, is all that's needed for them to feel joy. At the same time, I don't envy them because receiving their joy also brings it to me in a way I never experienced--especially here in Sitka--before I had kids.

When I used to come up, there was a loneliness and ennui that have now been drastically reduced by the companionship of other mothers who are close in proximity and in heart. Moms whose husbands fish/fly/leave in the night to rescue other men out in dangerous water or compromised vehicles, women who understand what it's like to have to give oneself entirely here to what sometimes feels like "a man's world." The truth is that this island is mostly an island of women. The men are, in large part, where we cannot reach them. Because I love my husband and because I tend to drink from the cup of never-enough, I believe his distance in time and space is what makes this place hardest.

What is not hard is knowing that we're giving our girls something refreshing and real instead of going to the pool every day (which is what I, in all truth, want to be doing). Greased watermelon contest over salmon fishing? Yes please! The smell of grilled burgers over fresh yellow eye we caught ourselves? Yep! Sweat over sweatshirts? Sold! But I see absolutely clearly that Anna and Zaley love the things we do here. The beach is full of rocks for gumming and throwing. Because of a warm spring here, the berries are already out, and we pick a bucket of them on the ten-minute walk down to our mailbox and eat them all up on the way back home. We go to the playground at 4 when the boats are coming in and the rain is minimal enough to dismiss. We take long baths, the three of us, when the wind is too much for me to get them layered and ready.

What is not hard is knowing that we're giving our girls something refreshing and real instead of going to the pool every day (which is what I, in all truth, want to be doing). Greased watermelon contest over salmon fishing? Yes please! The smell of grilled burgers over fresh yellow eye we caught ourselves? Yep! Sweat over sweatshirts? Sold! But I see absolutely clearly that Anna and Zaley love the things we do here. The beach is full of rocks for gumming and throwing. Because of a warm spring here, the berries are already out, and we pick a bucket of them on the ten-minute walk down to our mailbox and eat them all up on the way back home. We go to the playground at 4 when the boats are coming in and the rain is minimal enough to dismiss. We take long baths, the three of us, when the wind is too much for me to get them layered and ready.

Throughout every activity, because of our auditory-verbal therapy and because I want Anna to know what sounds mean and to be able to speak them clearly, I am the constant narrator. Pluck, pluck, pluck, we are plucking the berries. And, back and forth, back and forth go the swings, or, round and around go Zaley's brown boots down the spiral slide. In the bath, even though Anna doesn't wear her implants, I find myself still narrating as she slaps the water and pauses for effect. Like other mothers of deaf children told me, it is becoming second nature, this play-by-play voice of verbs and onomatopoeias. But for me, it's not just second nature--not here, not during this season. It's becoming an extra layer in this life, in this place, of layers. It keeps me here, on the floor with my kids, instead of in my head, in that down-south summer of my own childhood that I long for painfully with its chlorine and heat and picnics.

Throughout every activity, because of our auditory-verbal therapy and because I want Anna to know what sounds mean and to be able to speak them clearly, I am the constant narrator. Pluck, pluck, pluck, we are plucking the berries. And, back and forth, back and forth go the swings, or, round and around go Zaley's brown boots down the spiral slide. In the bath, even though Anna doesn't wear her implants, I find myself still narrating as she slaps the water and pauses for effect. Like other mothers of deaf children told me, it is becoming second nature, this play-by-play voice of verbs and onomatopoeias. But for me, it's not just second nature--not here, not during this season. It's becoming an extra layer in this life, in this place, of layers. It keeps me here, on the floor with my kids, instead of in my head, in that down-south summer of my own childhood that I long for painfully with its chlorine and heat and picnics.

Pitter-patter goes the rain, and splish-splosh goes Zaley in every puddle. Chh-chh-chh went the quillback we pulled up on the line today,  Zaley's first of the season, the mountains all around us in our own little fishbowl of sounds and beauty, struggles and contentedness and all kinds of water. I realize that being Anna's soundtrack is helping me to not borrow trouble. To tell Anna the story of here as it is happening, not as I once excepted it to, not as it maybe someday will be.

Zaley's first of the season, the mountains all around us in our own little fishbowl of sounds and beauty, struggles and contentedness and all kinds of water. I realize that being Anna's soundtrack is helping me to not borrow trouble. To tell Anna the story of here as it is happening, not as I once excepted it to, not as it maybe someday will be.